Piopiotahi: The history of Milford Sound

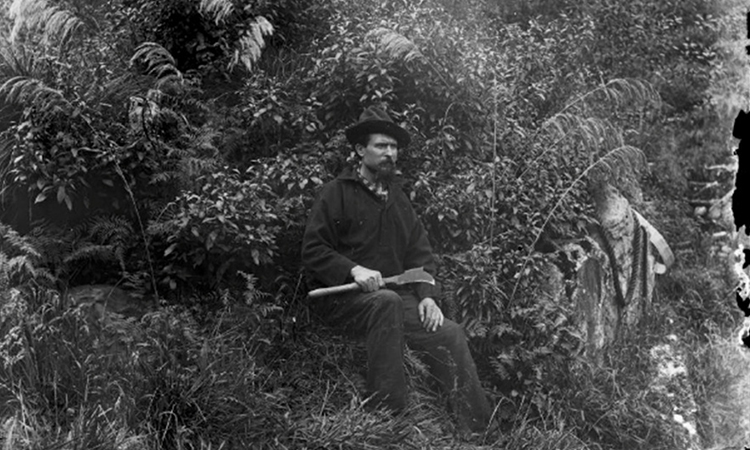

By the late 19th century, intrepid explorers in Fiordland were eager to share the grandeur of Milford Sound with the rest of the world. Pioneering guides like Quintin McKinnon began to establish tracks into the stunning, yet difficult to access, depths of Fiordland. In 1935, another ambitious pioneer, Henry Homer took on the challenge of drilling a tunnel through the sheer granite rock of the Darran Mountain Range to build a road to Milford Sound.

Today, MacKinnon’s Pass has become the Milford Track, one of the world’s finest walks. And the Homer Tunnel is the critical link providing daily vehicle access into one of the world’s most famous natural landmarks.

But before the tracks, roads and tunnels, Milford Sound was considerably less busy, home to an unimaginable population of birds and often visited by Māori hunters in search of prized pounamu. The dense native bush and challenging weather of Milford Sound is what ultimately saved it from the logging and development of the day. Today, much of Milford Sound’s important geological and ecological heritage is preserved along with the legends and stories sacred to local Māori. Here, we take a look at how Milford Sound was formed as well as its rich and fascinating history.

How Milford Sound was formed

Despite being known around the world as Milford Sound, New Zealand’s most popular natural landmark is misnamed. Just like its neighbour, Doubtful Sound, Milford Sound is not a sound, but a fiord.

So, what is a sound? A sound is formed when the sea floods a river valley and is typically characterised by a wide, gently-sloping valley. A fiord is often steep and narrow. New Zealand’s 14 fiords are all found in the South Island and are vast coastal inlets of water created by glacial movement. Around 15,000 – 75,000 years ago, glaciers made their way down the mountains to the sea. As the glacier melted or retreated, the sea flooded the valley left behind.

Crystalline and granite form the primary rock types in Milford Sound. These hard rock types withstood the strong carving movement of the glaciers to form the towering walls of the fiord and cascading waterfalls. Milford Sound Piopiotahi is also home to deposits of bowenite rock, known to Māori as tangiwai, a lighter version of the well-known greenstone or pounamu.

Standing like the mighty guardian of Milford Sound is the 1,692m-high (5,551 ft) Mitre Peak. Its sheer cliffside falls directly to the water and creates a dizzying first impression for any visit to Milford Sound.

The legend of Piopiotahi

Before Europeans began visiting Milford Sound for sealing, whaling, gold-prospecting and tourism, Māori considered it a sacred area blessed with an abundance of food and pounamu (greenstone). Milford Sound is believed to have been discovered by Māori over 1,000 years ago, although few lived here permanently instead visiting for hunting, fishing and gathering pounamu.

The Māori name for Milford Sound is Piopiotahi, meaning single native thrush. The South Island piopio is a native bird which is now extinct. The story of the thrush comes from the legendary tale of Maui, the demi-god, and his battle with Hine-nui-te-pō, the goddess of death. When Maui died in his attempt to gain immortality for mankind, a piopio is said to have flown south to Milford Sound to sing and mourn the loss.

According to Māori legend, Piopiotahi was carved out by the great god Tu-te-raki-whanoa, as he shaped the Fiordland coast with his adze (carving tool). He worked with his adze to create Preservation Inlet and Dusky Sound but saved his best work for Piopiotahi. Tu-te-raki-whanoa desired a place which would be rich with fish, birds and safe waterways and so he created Milford Sound. The imposing high cliffs of the fiord were his most spectacular work.

Tu-te-raki-whanoa’s work did not go unnoticed, and soon Te-Hine-nui-to-pō visited and proclaimed the area so beautiful humans did not deserve to linger here. Her solution was to release namu, the mischievous sandfly to deter anyone overstaying their welcome. Today, the sandflies still cause havoc for anyone who visits.

Piopiotahi has always held great importance for Māori because of its deposits of precious pounamu, specifically tangiwai greenstone. This most ancient form of greenstone is clear like glass and ranges in colour from olive-green to bluish-green.

How Milford Sound got its European name

The name Milford first appeared when sealer John Grono sailed past the fiord in 1823. Unsure about the narrow entrance, Grono never entered but took the time to name it Milford Haven after his Welsh homeland. Even Captain Cook missed the wonder of Milford Sound, instead sailing past its dubious entrance twice during his southern explorations.

In 1851, Welsh explorer John Lort Stokes named the vast inlet Milford Sound and this English name has stuck. But Stokes didn’t quite get it right when he proclaimed Milford a sound when it is, in fact, a fiord. In an attempt to rectify the anomaly, the entire area was named Fiordland.

Timeline of tourism in Milford Sound

1300-1500: First people step foot in Milford Sound

Early Maori inhabitants of the South Island– the Waitaha people, were believed to have settled in New Zealand in 1350. This tribe may have been the first people to step foot in Milford Sound.

1773: Captain Cook visits Fiordland

Captain Cook and his crew were the first Europeans to visit Fiordland, spending five weeks in Dusky Sound. Cook’s maps and descriptions soon attracted sealers and whalers who formed the first European settlements of New Zealand.

1809: First European to enter Milford Sound

Welsh sealer John Grono found himself in a storm on the Fiordland coastline, and fearing he would lose his ship and crew on the shores of Anita Bay, sailed into a small entrance that opened on his left. That entrance was Milford Sound, and Grono aptly named his spectacular find Milford Haven, after a place in his Pembrokeshire homeland.

1851: Milford Sound gets its name

Another hardy Welshman John Lort Stokes anchored his ship the HMS Acheron in the fiord. It was he who changed the name to Milford Sound.

1877: Milford’s first European resident

A tenacious Scotsman Donald Sutherland was Milford Sound’s first European settler. Following initial exploration, Sutherland decided to build a hut in Freshwater Basin and for the next forty years, he called the area home.

1880: Discovering the waterfalls of Milford

Donald Sutherland together with John McKay, a fellow prospector and friend, discovered the Sutherland Falls in 1880. News of these extraordinary falls spread quickly. Not long after, Milford Sound’s first hotel was built.

1888: Works starts on a track to Milford Sound

The New Zealand Government commissioned Sutherland to begin cutting a track from Milford Sound up the Arthur Valley towards Sutherland Falls.

That same year, Quintin MacKinnon, pioneer explorer and surveyor, was commissioned to complete the track from Lake Te Anau up the Clinton Valley to meet the path cut by Sutherland. MacKinnon Pass (1,154m) became the highest point on the Milford Track and the formation of the first vital land link between Milford Sound and the rest of the world. Quintin MacKinnon became the first guide on the track.

1889: The idea of a tunnel is born

A gold-panner and keen explorer William (Harry) Homer discovered the Homer saddle above what is now, the existing tunnel. Homer suggested boring a tunnel through the saddle that would provide fast and easy access into Milford Sound. He estimated that the tunnel would need to be around 33m (100ft) long to achieve his dream.

1914: Walking tracks, tour boats and tourism

Milford Sound had become a popular holiday destination, despite the challenges of getting there.

1929: Work on the Milford road begins

200 men carrying shovels, handsaws and wheelbarrows and a team of horses began the arduous task of completing the road to Milford.

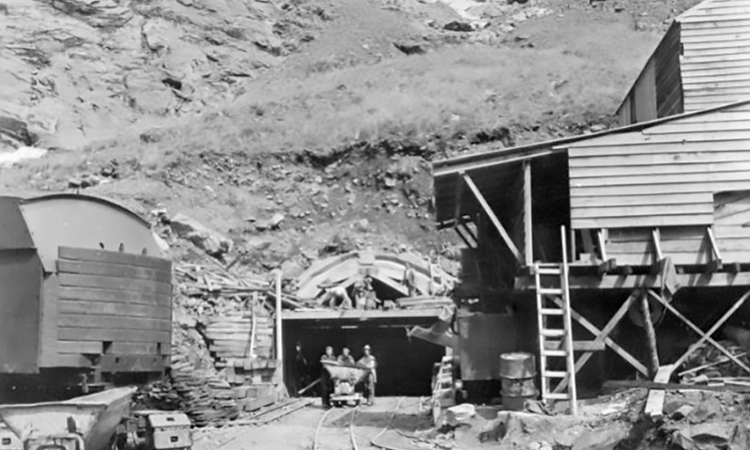

1933: Work commences on the tunnel

Led by John Christie, a Public Works surveyor and experienced climber, a team of surveyors climb the Te Anau side of the saddle. They set the top markers and then abseil down the Milford side, via the steep and precarious Grave Talbot track to complete the triangulation required.

1942: Breakthrough!

The tunnel breakthrough is made, and the first and only land link to Milford Sound is achieved.

1952: The creation of Fiordland National Park

Fiordland is officially constituted as a national park, and an area of around 1.2 million hectares is set aside for preservation.

1953 – The Homer Tunnel is completed

The Milford road was, and still is, one of New Zealand’s most expensive construction projects.

1986: Fiordland is recognised by the United Nations

Fiordland National Park becomes a World Heritage Area Listed area. It is described as a ‘superlative natural phenomena’ offering ‘outstanding examples of the earth’s evolutionary history’.

1990: Fiordland becomes part of the Te Wāhipounamu World Heritage area

Along with Aoraki/Mt Cook, Mt Aspiring and Westland National Parks. Te Wāhipounamu – known to the original Māori inhabitants as Te Wāi Pounamu – is a 2.6 million hectare site covering almost 10% of New Zealand’s total land area.

1990: Private tourism companies take on New Zealand’s special sites

The New Zealand Government sells its tourism assets to private companies including Red Boat Cruises, now known as Southern Discoveries.

1998: The Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act

Ngāi Tahu – the principal tribe within the South Island –have their rights to the land protected by law.. As a consequence of this Act, the Government can no longer dispose of any land in the South Island without first consulting Ngai Tahu for first refusal.

Today: Milford Sound’s appeal continues

Approximately 10,000 people walk the Milford Track each year and nearly 1,000,000 visit Milford Sound.